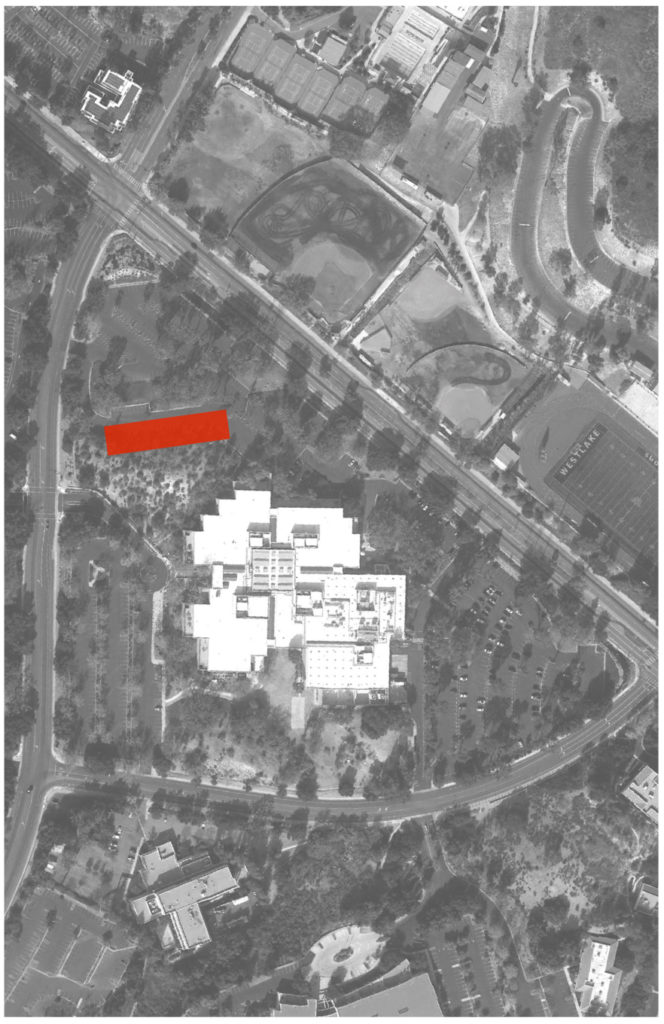

There are towns in Southern California that take pains to preserve the iconic environmental features that originally defined the region, such as rolling grass-covered hills dotted with clusters of Oak trees. When the head of a major real estate development company called upon TCA’s Hospitality Studio to help situate a new hotel on one of their prime commercial office properties, they were seeking to resolve their own land use needs with that town’s preservation-minded zoning criteria. Siting for the new development would have to meet strict parameters: hundred foot setbacks, a height limit that implied a three story maximum and, while retaining as much parking as possible, preserving more than a hundred mature Oak trees. So, where could one place a new hotel, which most major brands would say needs to be at least four stories to meet their typical guest room count, while also preserving the intrinsic qualities of the site?

Setting the hotel into the base of a hill anchors the building on the site, preserves the Oak trees, frees up the remainder of the parcel for parking, and addresses the town’s planning rules that rigorously restrict building height and visibility.

Setting the hotel into the base of a hill anchors the building on the site, preserves the Oak trees, frees up the remainder of the parcel for parking, and addresses the town’s planning rules that rigorously restrict building height and visibility.

The answer lay in a site plan the owner had already presented to TCA, on which another architect placed a hotel, in the conventionally suburban manner, smack dab in the middle of the parcel and surrounded with parking. But this predictable strategy took one bold exception to the existing context, proposing to excavate a good portion of a forty foot high, rocky hill that separates the hotel parcel, on the northern tip of the site, from an existing office building to the South. If the owners were willing to expend the resources required to carve this much earth away just for parking, then, reasoned TCA’s designers, why not use that cleared space for the hotel itself? The architects pointed out that making this one straightforward move addressed all the important site restrictions in a single stroke.